Resources for Online Interviewers

By Janet Salmons, Ph.D.

How will you use information and communications technologies (ICTs) to conduct interviews?

The saying goes, "If a farmer fills his barn with grain, he gets mice. If he leaves it empty, he gets actors." Like actors, researchers are always looking for an opening. If a means for communication opens, intrepid researchers will find a way to adopt it to their own objectives, shaking up the academic status quo along the way. (Salmons, 2010)

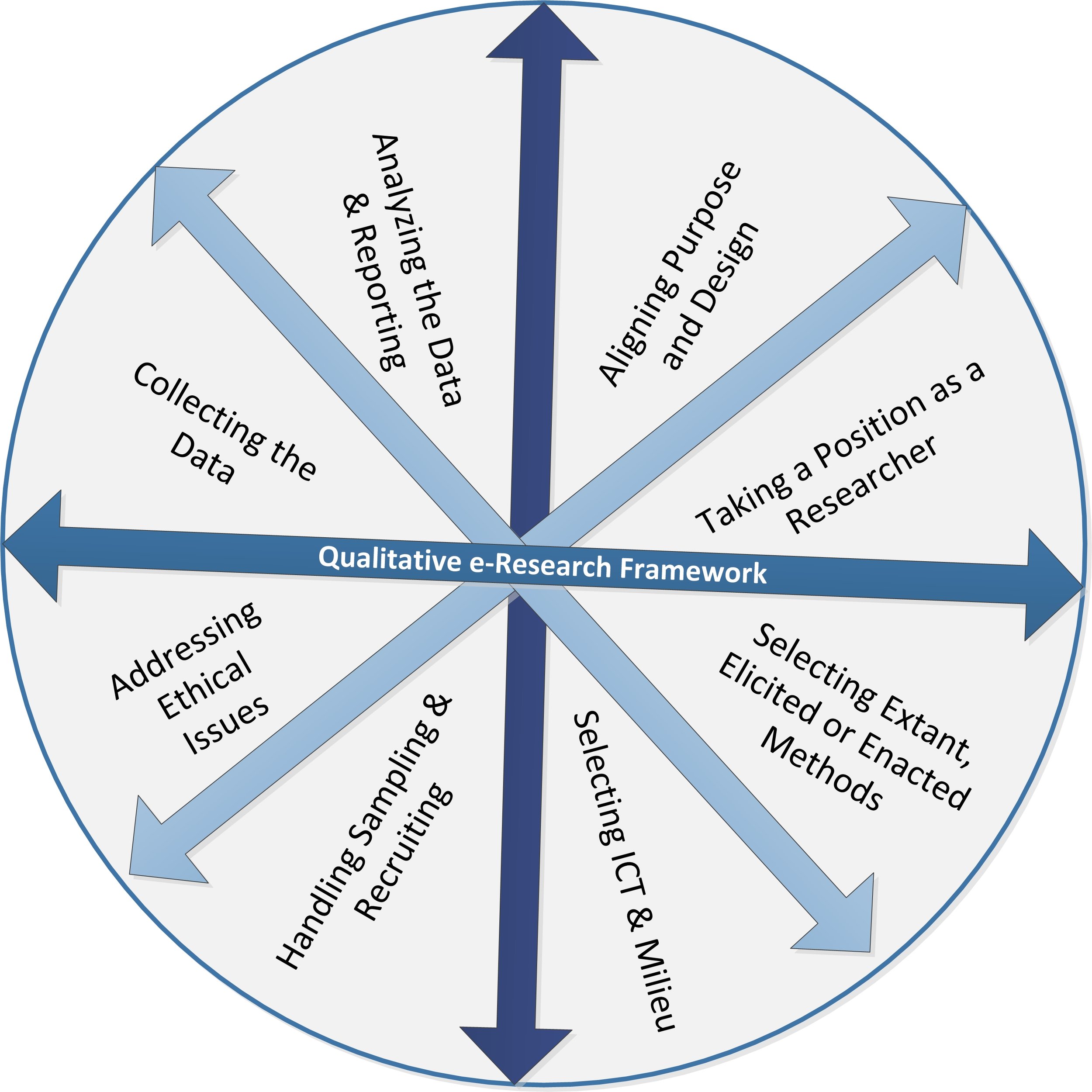

That is how I prefaced my first book, Online Interviews in Real Time* and since then qualitative and quantitative researchers have blown the roof off the proverbial barn. We've discovered diverse ways to use technology to inspire or further research. We've seen various types of e-research emerge, with their own approaches, variously called Internet research, online research, virtual research or digital research. I’ve categorized approaches by the way information and communications technologies (ICTs) are used as the medium, setting, and/or research phenomenon (Salmons, 2022).

What role do information and communication technologies play in the study? (Salmons, 2022)

Some researchers use ICTs as a medium through which they reach and interact with participants, be it in 1-1 or group interviews, or online questionnaires or surveys. Researchers use ICTs as a medium through which to access archives, datasets, and other contemporary or historical records.

Other researchers are interested in communication via a platform, program, social networking site or online community, virtual world or game. These researchers use ICTs as the setting. Within an electronic setting users could be discussing experiences or events in the "real" world or the connected world. The setting is selected because it is a place where people are discussing the problem central to the study. The researcher might collect data directly (with appropriate consent or agreements) or use the setting to recruit participants. The setting may have limitations or affordances that allow for visual, verbal, and/or text-based interactions.

A third type of researcher are interested in the programs, sites, or platforms themselves, in the ways humans use technology, how the features or characteristics of the ICTs work. For these researchers, the technology itself is central to the research phenomenon they want to understand.

Hypothetical example:

For example, let's say a researcher is interested in local grassroots politics. She could use the Internet as a medium, a communication channel for interviews with activists. She doesn’t care what features the ICT has, she simply wants an accessible tool.

If she sees that activists are using particular channels to inform the public and generate interest, she might decide to focus on a particular setting for activists' mobilization, perhaps studying posts on YouTube, Facebook, Medium, or blogs. She might use an electronic setting for an experiment, or for experiential or creative methods.

Alternatively, she might be interested in the user interfaces and features that allow users with no knowledge of programming to create and promote their own content. She might want to compare uses of text-based versus multimedia posts, the process of virality, linkages across platforms, use of mobile devices, or other ICT phenomena related to activists' uses of technology. This researcher or research team might combine one or more options, and mix qualitative and quantitative approaches to gain a comprehensive perspective on the research problem.

Janet Salmons with Doing Qualitative Research Online.

These resources might be helpful if you are planning to collect data by conducting interviews online:

Qualitative Online Interviews includes guidance on designing and conducting studies using a wide range of synchronous and asynchronous technologies for interviews, creative and visual methods, and observations.

Cases in Online Interview Research includes contributed examples that use a wide range of technologies, from blogs to videoconferencing to virtual worlds, with analysis of decisions and methods.

Doing Qualitative Research Online goes a step further, with inclusion of methods that use extant, creative and performative ways to use technology in data collection. The second edition of Doing Qualitative Research Online is now available. Find more resources for teaching and learning here. Find short video explanations for key concepts in these books on this YouTube playlist.

The Little Quick Fix book, Gather Your Data Online offers an overview of key concepts and practical tips. This book is the basis for a new interactive course on Sage Campus.

Use the code COMMUNIT24 for 25% off through December 31, 2024 when you purchase the book from Sage.

Access e-books and download chapters!

Doing Qualitative Research Online and Cases in Online Interview Research are available on SAGE Research Methods. That means you can access the books in full, and download chapters as PDF files. In addition, see the broad E-Research Reading List, Social Media Research Reading List and the E-Interview Research Reading List. If you would like to access these SAGE e-books, articles, case studies, videos, and datasets, explore SAGE Research Methods through your academic library, or with a free trial.

More about methods for online interviews: Open access articles

Lindsay, S. (2022). A Comparative Analysis of Data Quality in Online Zoom Versus Phone Interviews: An Example of Youth With and Without Disabilities. SAGE Open, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221140098

Abstract. Qualitative researchers are increasingly using online data collection methods, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. I compared the data quality (i.e., interview duration, average number of themes and sub-themes, and inaudible words) of 34 interviews (29 conducted by Zoom (16 with camera on, 13 camera off) and 5 conducted by phone) drawn from a study focusing on youth’s coping experiences during the pandemic. Findings showed that phone interviews had a longer duration compared to Zoom. However, phone interviews had a similar average word count to Zoom interviews (with the camera on). Zoom interviews conducted with the camera off were shorter in duration than interviews with the camera on. The number of themes was similar across the different interview formats but there were fewer sub-themes for Zoom interviews with the camera off. The findings suggest that Zoom interviews conducted with the camera off could affect the data quality. This research also emphasizes the importance of giving participants choice in the format of their interview to allow for optimal sharing of experiences while enhancing the equity, diversity and inclusion of the participants.

Lobe, B., Morgan, D. L., & Hoffman, K. (2022). A Systematic Comparison of In-Person and Video-Based Online Interviewing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221127068

Abstract. Due to the increasing popularity of online qualitative interviewing methods, we provide a systematically organized evaluation of their advantages and disadvantages in comparison to traditional in-person interviews. In particular, we describe how individual interviews, dyadic interviews, and focus groups operate in both face-to-face and videoconferencing modes. This produces five different areas for comparison: logistics and budget, ethics, recruitment, research design, and interviewing and moderating. We conclude each section with set of recommendations, and conclude with directions for future research in online interviewing.

Opara, V., Spangsdorf, S., & Ryan, M. K. (2023). Reflecting on the use of Google Docs for online interviews: Innovation in qualitative data collection. Qualitative Research, 23(3), 561-578. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941211045192

Abstract. Google Docs is a widely used online word processing software. Despite its broad popularity in business and education, Google Docs is under-utilised as a tool to facilitate qualitative interviews within research. In this article, we reflect on our experiences as two PhDs using Google Docs to conduct synchronous, online, written interviews. We present two case studies, which, to our knowledge, are the first to utilise Google Docs to conduct web-based written interviews. In doing so, we (a) outline the development and implementation of the methodology, (b) highlight the key themes we identified when considering the benefits and challenges of conducting interviews using this technology and (c) discuss possible future uses of the methodology. We argue that synchronous web-based written interviews via Google Docs offer unprecedented opportunities for qualitative research.

Methods and studies: Online focus groups

Brown, C. A., Revette, A. C., de Ferranti, S. D., Fontenot, H. B., & Gooding, H. C. (2021). Conducting Web-Based Focus Groups With Adolescents and Young Adults. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406921996872

Abstract. This methodologic paper aims to update researchers working with adolescents and young adults on the potentials and pitfalls associated with web-based qualitative research. We present a case study of synchronous web-based focus groups with 35 adolescents and young women ages 15–24 years old recruited from a clinical sample for a mixed methods study of heart disease awareness. We contrast this with two other studies, one using asynchronous web-based focus groups with 30 transgender youth ages 13 to 24 years old and another using synchronous web-based focus groups with 48 young men who have sex with men ages 18 to 26 years old, both recruited via social media. We describe general and logistical considerations, technical platform considerations, and ethical, regulatory, and research considerations associated with web-based qualitative research. In an era of technology ubiquity and dependence, researchers should consider web-based focus groups a potential qualitative research tool, especially when working with youth.

Do you think about research questions as an insider, outsider, or somewhere in between? Why is positionality important in online research?