The Language of Academic Assessment

By Alex Baratta, PhD Senior Lecturer, Manchester Institute of Education

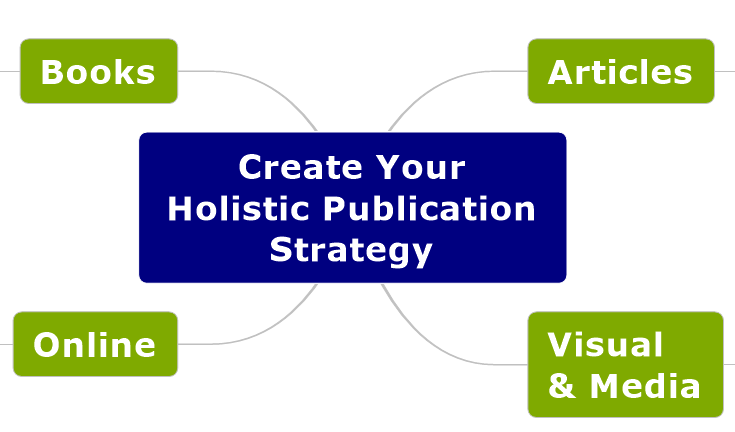

Dr. Baratta is the author of How to Read and Write Critically (2022) and Read Critically (2020). Use the code MSPACEQ423 for a 20% discount on his books.

When you write your academic essays, you will be judged on several criteria. These include the essay structure, your demonstration of knowledge and understanding and also the language you use. Language is a broad term and can include the level of formality or informality (e.g., The police officer arrived versus the cop showed up), and the use of technical language based on your major (e.g., words such as zygote in Biology and hypercorrection in Linguistics). A central aspect of your language use, however, will be the need to use standard English. Let us first consider the sentences below before discussing standard English. Which of the sentences below are ‘correct’?

Give us them books

It were cold yesterday

That is well sick

More Methodspace Posts about Academic Writing

She be complaining

It was cold yesterday

Some of the sentences above might ‘sound’ strange and/or be unfamiliar to you. But the question is whether they are correct or not. The truth is, yes – they’re all correct. A more accurate term, however, would be grammatical. This means that all the sentences above are using a form of grammar that is predictable, systematic and widespread, used by a certain group(s) within society. Thus, all the examples above rely on grammatical rules. The first two examples would be used in England, more so the Northwest. Example three is perhaps used more widely across England, even Britain, but spoken as a form of youth culture. Example four is African American English, or Ebonics, with the final example what we call ‘standard English’.

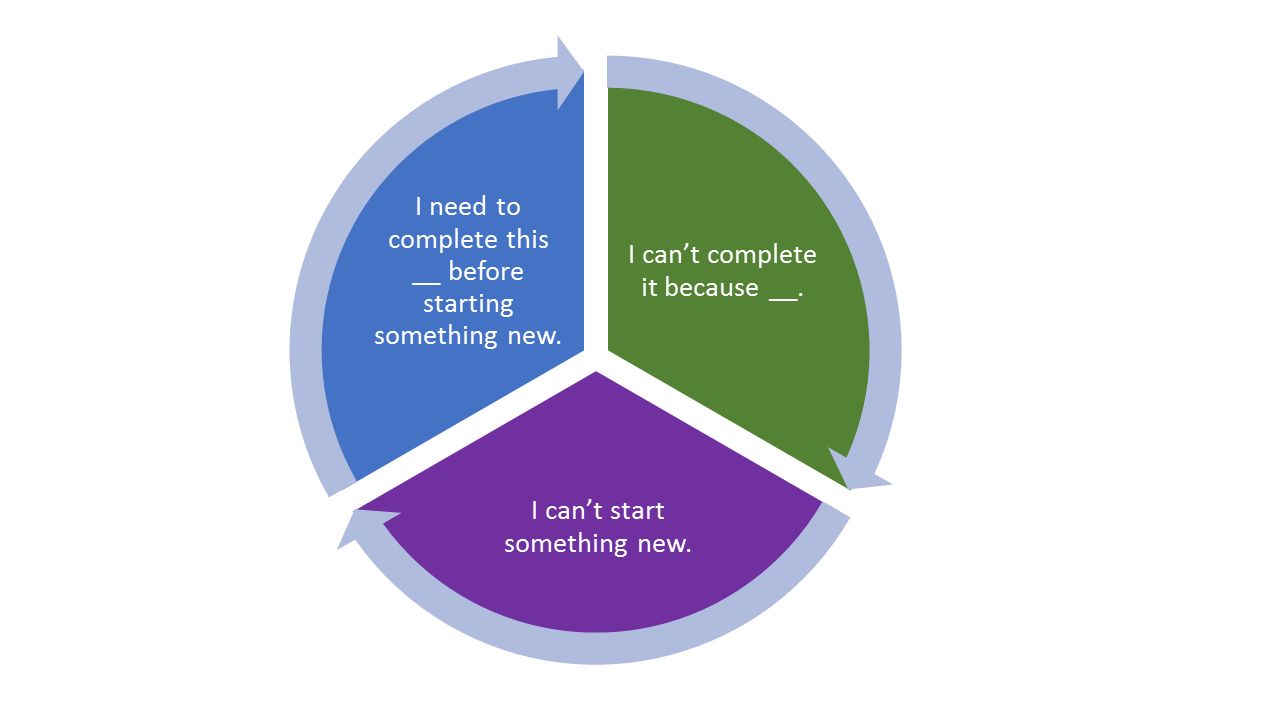

Given that all the examples, including the non-standard English examples, are all grammatical, why then are non-standard Englishes often viewed as incorrect or even ‘defective’ somehow? This is unfortunately due to several reasons, none of which hold water. Some people, including teachers, are focused so much on the need to teach children to read and write standard English that all other varieties, by default, are labelled as incorrect, or at least as something to avoid. However, all language varieties have a time and place. Indeed, if using non-standard English with your friends or family, a sudden switch to standard English might suggest you are putting on unnecessary linguistic airs and graces.

Another reason for the negativity is that it is standard English which is used in ‘official’ contexts. This is not just academic writing, but also includes government reports, bank statements, contracts for a mortgage and so on. These are all prestigious contexts, those that even suggest power. Thus, the implication might be to some, incorrect though it is, that non-standard English is simply less prestigious and carries no societal weight.

Despite the word ‘standard’ suggesting some kind of linguistic royalty, standard English is neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad’ – this applies to all varieties of any language, not just English, and both standard and non-standard varieties. In Britain, the country that gave us English, there was a great deal of variety with earlier forms of English hundreds of years ago, as is still the case. But there was no need for a singular form to be chosen for mass communication, and thus, no standard existed as such, only varieties. However, once the printing press came about, so did the need for printing in a singular variety of the language, in order to save on printing costs and make life easier. It is for this reason that one variety needed to be chosen over all others. This variety was based on London English. This decision was not made because London English had grammar and vocabulary that was somehow more ‘logical’ or ‘better’ than all other varieties of English. Rather, the decision was based on the simple fact that as the capital city, London, like most capital cities, was where the power was – political power, economic power and higher education. Thus, the form of language used by the powerful in society, concentrated in one major city, meant that the language itself became powerful. But any power standard English has is based, therefore, on politics, and not based on linguistic reality.

Standard English has a use of grammar and vocabulary which simply differs from non-standard varieties, and vice versa. But difference is not deficit! Thus, get into the habit of recognising the different varieties of English, and other languages, and from here, appreciate the contexts in which their usages differ. While standard English is the appropriate variety to use for academic writing, non-standard English might work much better for a personal blog, and definitely within poetry. Some final examples are provided below. Remember! View the examples as all being grammatical, because they are, with none of them ‘better’ than another. From the examples you can also perhaps learn the grammatical rules of the non-standard varieties:

Standard English He eats

Ebonics He eat

Standard English Police officer

Liverpool dialect (a city in England) Bizzie

Standard English He was hungry

Manchester dialect (a city in England) He were hungry

You get the idea. And one implication of standard English is that it is widespread across the country, whether the USA or Australia. This means it is understandable to many people, another reason being that this is the variety taught to us in school. Non-standard varieties, or ‘dialects’ as they are also known, are, by implication, used in only a certain region of a country and/or by a certain group (e.g., young people). The implication for this is that given their less widespread usage, and by not being taught in schools, there is less understanding, and appreciation, for these varieties compared with standard English. But now you have some linguistic understanding of the subject, get used to using standard English as and when it’s needed, but by all means break out non-standard English when the context calls for it to be deployed.