Research & Writing, Creativity & Collaboration

by Janet Salmons, Research Community Manager for SAGE Methodspace

Dr. Salmons is the author of Doing Qualitative Research Online, which focuses on ethical research and writing, and What Kind of Researcher Are You? which focuses on researcher integrity. With the code MSPACEQ322 (through September 30, 2022) or MSPACEQ422 (Through December 31) you receive a 20% discount when you order the books from SAGE.

This post is from the Methodspace archives, from the 2020 MethodSpace AcWriMo. For that we aimed to catalyze new thinking about publishing trends (and what they mean for academic writers.)

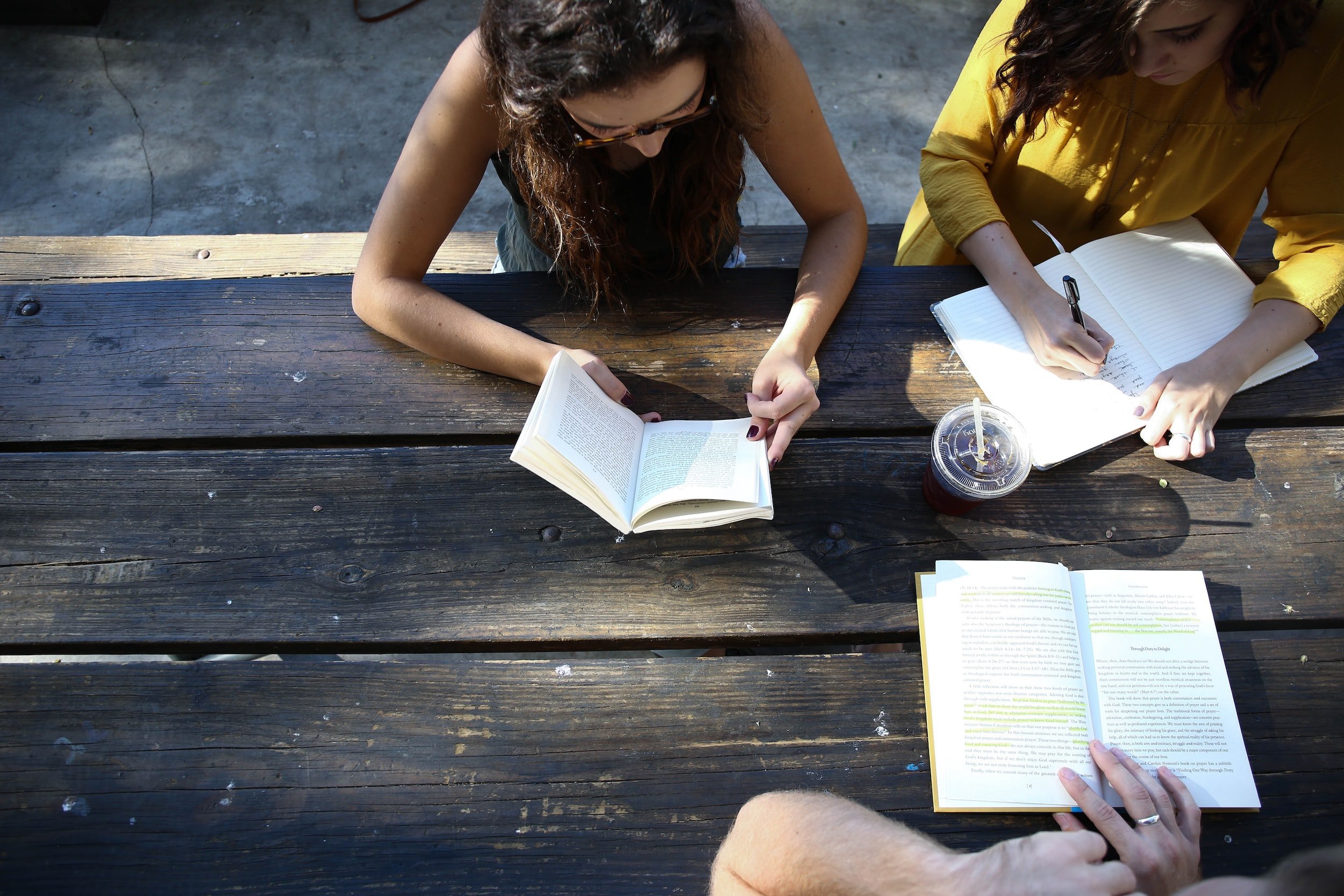

One publishing trend is toward collaboration, to bring diverse perspectives, disciplines, and skills to our projects. Another is toward creativity, in more open and flexible thinking as well as presentation modes. This post offers an example of a collaborative process at work.

When MethodSpace contributor Jane Shore sent me this "Creativity through Community" Venn diagram, I was struck by the placement of inquiry along side intuition and improvisation. I thought it would an interesting springboard for a shared post.

I invited Narelle Lemon, my co-author on Reframing and Rethinking Collaboration in Higher Education and Beyond, to discuss her response. I wrote about how the graphic spurred my thinking. I sent both of our pieces to Jane, who elaborated on her model with a new introduction. This longer-than-usual post contains all three of our contributions. If you have thoughts you'd like to share about intersections of improvisation, intuition, and inquiry, please use the comment area to share your ideas or examples.

Introduction by Dr. Jane Shore

When we hear the word creative, we tend to imagine a skill held tight by only some- artists, authors, photographers, performers, those who use “creative” as a noun. We tend to think there is perhaps a type, a creative who moves in the world differently than others.

But creativity is something we all have, and we all can cultivate, grow and harness. These are connective spaces, the bridges between thoughts, flashes of inspiration among people or ideas, threads that allow cross over from one into another. We all use creativity to span boundaries and connect diverse concepts, to solve complex problems and accelerate innovation. And we argue this does not happen without others.

Inspired by Natalie Nixon’s theories shared in her recent book, The Creativity Leap, creativity and innovation are a result of three tactical routes or cues- improvisation, intuition and inquiry. Humans naturally are able to think expansively and in novel ways, but learning how to harness creative force requires competency.

To contribute to Nixon’s theory, we suggest that creativity and innovation only grow through creative collaboration, and at times creative friction, with community. Building on her work, there are three elements.

Inquiry in connection with others. In his book The Powers of Two, Joshua Wolf Shenk draws on scientific research to craft a persuasive and compelling argument for the social foundations of creativity. It is not just inquiry, but dialogue, experiences in the world, conflict and friction that allows bridges the gap between what you know and what you currently don’t understand. Nixon describes, “It is the practice of honing your ability to frame and reframe questions, to use questions as a way of thinking through and processing.” We love this description, and would add that this does not happen inside the mind of a singular genius, a singular artist, thinker or doer. Inquiry in connection with others is a route of creativity.

Improvisation with others. Many professions are all about improvisation. Architects, astronauts, artists, researchers and teachers- there is improvisation threaded into all. But building on ideas within minimal constraints grows in new ways only in community. The concept of burstiness, that bouncing of ideas like one does in jazz ensembles- is a social construct. It requires playing leading and supporting roles, requires psychological safety and lowered affective filters. It requires a group that is reflective and reflexive.

Intuition. This element of creativity is the force that allows us to “go for it.” So frequently we think of intuition as only a message in our gut. But in reality, when intuition leads to action it is most frequently done so in the presence of others. There is a certain amount of background processing and a certain combination of a safe space to jump, a balance of this could work and YES IT COULD. We argue that intuition is a combination of your creative instinct and that which has been cultivated in the community of others.

Creativity by Dr. Narelle Lemon

Creativity is an integral part of me. It is a strength. It is a hobby. It is a part of my job. It inspires me. It calms me. Creativity for me is about creating and combining things in imaginative ways. Sometimes it is to produce something new. Sometimes the act of creativity helps me is to rethink something. And sometimes it is not related at all to the “doing” it is a “being". In this way I think about the intersection of this visual representation and the act of “background processing”.

Making as a part of creativity has always accompanied me. Whether it was music, painting, drawing, photography, writing, sculpture, making things with found objects, or knitting - one or more of these ways of expressing myself and exploring has always been present daily. Navigating COVID-19 while living in Melbourne has for me revealed the complexity of the act and indeed gift that creativity gives. During self-isolation under a strict curfew with limitations to how and when you can leave the home, making for me has been located in working with wool and knitting. I’ve made 2 blankets, 3 beanies, and numerous scarfs that I have lost count. But the making has been my way of processing. It has been my constant in times of foggy brain, zoom fatigue, and shifting ways of working that have caused me to relook at my boundaries, rituals and routines for writing and indeed carrying out research. Knitting and working with wool, has slowed me down. It has been a calming influence. It has allowed me to subconsciously process my research, to problem solve a solution to present to my co-researchers, and it has allowed me to step back and just be. To be in the present moment.

Writing is a creative outlet, yes, but it is the making that has allowed me to create my research; to process and make connections. The act of making, using my hands, takes me away from the thinking about my research, the paper, data, analysis, etc. This slowing down and being allows me to process. As I work currently with new data, I am reminded of how this act allows me to slow down and be with my data. I process every word, not rushing. Rather embracing time with the words my participants have shared. Making connections. Just letting connections come, as knitting is about the knitting itself, I don’t do it to think, but it does help with my thinking. The act of slowing down and being present with the texture of the wool, the pattern I am knitting, and the movement of yarn with needle, I allow connections to emerge. The act of making fosters my thinking. If I knit after I have coded, thinking I am finished, I am always surprised at how my coding develops further. I can see intricacies, differences and subtleties that I hadn’t noticed before. They pop into my head, like a gift from that foggy part of my brain that just hasn’t made the connection. As I knit my brain almost knits further connections I hadn’t been able to see in that moment of time. You see, knitting helps the processing. A processing that is not always present when we are researching. I’m invited to think, what is it the data is telling me? How can I use my creative being to help me process the research process itself, methodology or epistemology? What am I gifted with as I honour this time to process? How does this act of creativity enhance my research?

I invite you to consider: How can you use this way of being to help me as a researcher? How can an act of creativity foster you as a researcher?

Improvisation & Inquiry by Dr. Janet Salmons

When I look at Jane’s Venn diagram, the improvisation/inquiry relationship jumps out. As a music lover, I think about how a combo can improvise together and avoid cacophony. A nod or eye signal lets the sax know it is time to take over from the bass. How? They have charts and shared vocabularies that let them cut loose, within an agreed-upon framework.

Now let’s look at inquiry. Some use the term inquiry to describe a study, but I think of it as the open, curious mindset that precedes research designs and plans. What do we want to know, and are we open to finding out that our preliminary thinking and hunches about the problem are wrong?

What happens when we try to bridge improvisation and inquiry? Clearly, we need agreed-upon frameworks. We need more than a general sense of a problem and question: we need to be able to communicate the purpose of the study, potential ethical risks, and general process, so that others associated with making the research happen can take their parts. Even a seemingly solo research project involves librarians, archivists, gatekeepers, and/or participants. They need their charts, they need to know what key are we in.

Given the state of the world and increasingly inter-related and electronically connected nature of modern life I think it is too limiting to study narrowly conceived questions. Can we know the dimensions of the problem when we are at the design stage, perhaps somewhat removed from the way this problem plays out in the lived experience of real people? Might a health problem really be an economic problem, a social problem really a culture clash? Don’t we need to be able to improvise when we realize there are significant directions that must be pursued—perhaps beyond our disciplinary lenses—to accurately understand the research problem? Of course, some methods allow for improvisation. Semi- and unstructured interviews allow the researcher to shift in response to points made by the participant, for example. Creative methods invite participants to be improvisational in the ways they express themselves. I’d like to explore going further, to think improvisationally about inquiry at a more conceptual level. How can we stretch our thinking about epistemology and methodology, and the overarching meaning of research? Is it truly about creating new knowledge and deeper understandings? If so, how can we find ways to frame inquiry that allow for improvisation? If you need some inspiration while you contemplate these questions, check out some masters of improvisation on this Spotify playlist. (You can listen with a free membership.)

Michelle Boyd answers a question about taking small steps to make progress on a large writing project.