Sharing Story Ownership in Qualitative Research

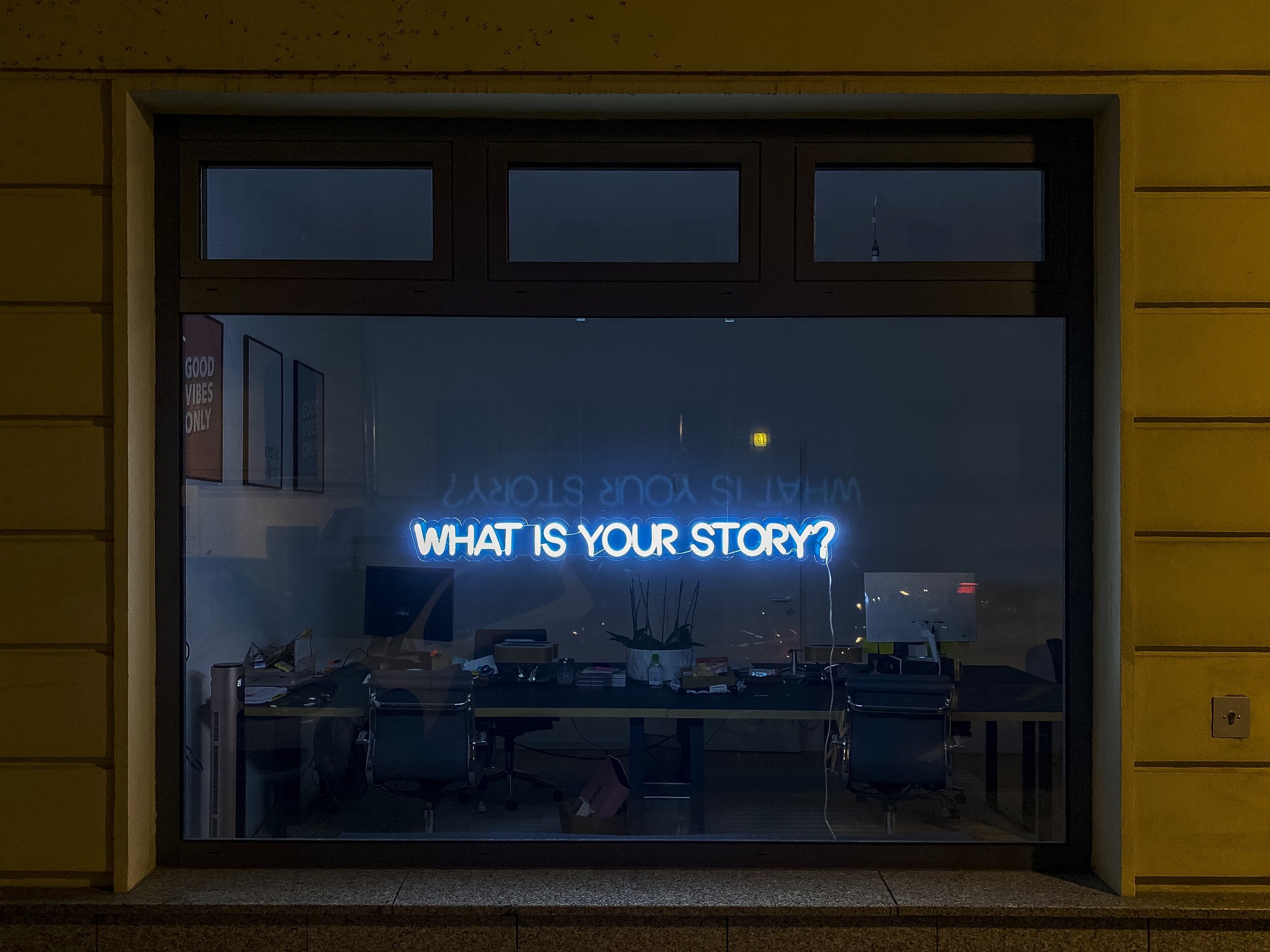

Whose story do you tell in a study? To whom does the story belong? How do you write a research story?

These questions arise as you start a research project, especially in social and behavioral science research. Often overlooked, researchers may, at the outset, develop a study without considering the storytelling approach and their specific roles as storytellers. Generally speaking, a quick scan of studies published in research journals, edited volumes, or even monographs, may reveal that explicit discussions about story ownership and clearly articulated roles in the research process tend to appear with less frequency.

In most scholarly investigations—as a very early research framework emerges with initially sketched research problem and questions—a good place to start thinking about what, who, where, and when to explore a phenomenon is with who’s a part of the work. With some exceptions, frequently, a researcher or researchers, research participants, and an audience of readers assume roles in a study and meaningfully—constructively—shape what’s presented in a final manuscript publication or paper presentation. That is, the broader contributions that you make through research work are not yours alone; they belong to and are owned by folks who participate in the research process, conceptualization to dissemination.

In naturalistic inquiry, researchers have lots of opportunities at multiple phases of the fieldwork process to invite not just members of the academy or colleagues in related fields to cowrite a research story but folks in groups or communities in local social scenes, including research participants, informants, and gatekeepers. Prior to the start of fieldwork, you are well positioned to seek input from research colleagues and informants alike. In the case of the latter, early work with individuals who are closest to research participants in your study can facilitate instrumentation and direct you to new leads that could reshape the focus of a study and phenomenon under investigation. Later, data collection, analysis, and interpretation offer you unique spaces to ask individuals to share more than just responses to questions or subjects of observations but also feedback to you in the research process, clarification of what they say in the context of field settings, discussion of meaning in emerging thematic patterns, and interpretation in draft and final write up of results. To this point, you may write a research story in a narrative structure. Golden-Biddle and Locke (2005, p.25) say that “stories provide a narrative structure for our work that arranges events and ideas according to some temporal sequencing of past, present and future.

”Working with a sensitivity to local customs, rituals, and traditions, consult folks as you move through fieldwork to confirm the events and ideas—and their sequenced order—are accurate from a local perspective. This is especially important when working with vulnerable, marginalized, and/or oppressed groups.

Once ready to disseminate, you can consider your story still in draft form—until the work has been scrutinized in the academic peer-review process and/or you have received feedback from folks you met in the field. At the start of fieldwork, thinking about this late-phase consideration in the research process can help you frame how you exit the field when data collection ends so that you leave tentatively—only to return later to share transcribed data files or thematic results in a member-check type activity.

So whose story do you tell in research work? Research participants, gatekeepers, informants, sponsors, readers, and you own the research story—so use strategies to gather and make sense of information for a collective story and tell it like it’s a shared narrative. Yours, theirs, and ours.

References

Golden-Biddle, K., & Locke, K. D. (2005). Composing qualitative research. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Learn about qualitative data analysis approaches for narrative and diary research in these open access articles.