Pedagogies of Care in Precarity

By Hiba Barek, University of Western Ontario, Immaculate Namukasa, University of Western Ontario and Sharon M. Ravitch, University of Pennsylvania

Sage Research Methods Community readers will recognize Dr. Sharon Ravitch, who served as a Mentor in Residence in March 2020 and has contributed significant posts, including ones on Flux Pedagogy. Dr. Ravitch is the author of Qualitative Research: Bridging the Conceptual, Theoretical, and Methodological (2020).

Education is, in its very essence, an act of care (Acevedo, 2020; Barek, 2020; Gay, 2018; Mortari, 2016; Noddings, 2003). The concept of care in education is not new (Acevedo, 2020). Ancient philosophers (e.g., Socrates, Plato, Aristotle) and contemporary scholars (e.g., Gilligan, Gay, Noddings) aver that education is meant to positively impact students’ lives which implies caring for the wellbeing of others (Mortari, 2016). Plato frames education as a moral endeavor in which educators exhibit deep care for student wellbeing with the fundamental role of supporting students to actualize their potential. The critical pedagogies of Paulo Freire, John Dewey, and other seminal scholars reveal “an underlying ethic of care” though their pedagogies are not framed explicitly as care pedagogies (Monchinski, 2010). The concept of care as an educative ethic was articulated only in the second half of the 20th century by Nel Noddings (1984).

Care is enacted across educational institutions in a diverse range of ways, illuminating that understandings of what supports students and their learning differ widely between communities and cultures in ways deeply affected by sociopolitical forces. Economic and political rivalries born of capitalism have created a competitive, transactional culture that teaches us to strive for maximum efficiency and not “waste time” on the relational, fostering a schooling culture of hyper-individualism. It is vital to reinterpret education and recalibrate schooling through humanizing perspectives of care (Gay, 2018; Montari, 2016; Noddings, 1992), especially in times of precarity such as now. During the COVID-19 pandemic, efforts to re-humanize education are being re-centered in education. For example, in the professional development of instructors at our universities, conversations about innovating teaching at the start of the pandemic have evolved into a focus on care in classrooms and pedagogical encounters. This has led to care pedagogies such as Trauma-Informed and Healing-Centered Pedagogy (Ginwright, 2018), Culturally Responsive Teaching (Gay, 2018), and Flux Pedagogy (Ravitch, 2020a).

In this collaborative piece written across two countries in pandemic, we introduce the concepts of pedagogy of care and the ethics of care (Noddings, 1984, 2003) that underlie care pedagogies. We highlight the primacy of action in pedagogies of care, and describe pedagogies of care in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic as a way to reimagine and build forward.

What is a Pedagogy of Care?

A pedagogy of care is a pedagogical perspective, an approach to teaching based on an ethic of care as both a moral imperative and pedagogical necessity (Gay, 2018). Ethics of care theory offers constructs for understanding the nature of teacher-student relationships (Barek, 2020; Noddings, 1992). Noddings (1992, 2003) identifies reciprocity in caring relationships in educational settings as the ultimate condition for learning and positive change. Scholars such as Noddings (2003), Freire (2005), Gay (2018) and hooks (1994) conceptualize teaching as an embodied practice of care. According to these scholars of pedagogy, care is not an easy, straightforward, unidimensional practice and, further, it necessitates action. A pedagogy of care emphasizes mutual respect and engenders authentic dialogue that attends to preconceived assumptions, enacts compassion, affirmation, and investment in transformative action (Noddings, 1984) and reciprocal transformation (Nakkula & Ravitch, 1998). Pedagogies of radical compassion and self-care such as Flux Pedagogy (Ravitch, 2020a; 2021) align with pedagogies of care and extend them into this moment of trauma—personal, familial, communal, intergenerational. Ethics of care and radical self-care frameworks are complementary and interdependent; together they create the conditions to foreground care in teaching, learning, and leading from pre-school through graduate school.

Ethics of Care in Education

Ethics of care theory is a framework for developing caring teacher-student relationships that support student achievement and wellbeing (Barek, 2020). Building on the work of Carol Gilligan (1982), a care theory pioneer in psychology, Noddings (1984) applies the construct of care to education. In schools, an ethic of care emphasizes reciprocal relationships between teachers and students based on mutual respect, authentic dialogue, and investment in knowledge for action (Barek, 2020; Noddings, 1984) with a shift from a focus on educators to foregrounding students (Noddings, 1984, 2003). Teachers who enact an ethic of care: 1) sustain care for student welfare, 2) work closely with and actively support students, 3) are responsive to students’ social and emotional needs, 4) design and enact student-centered curriculum and assessment.

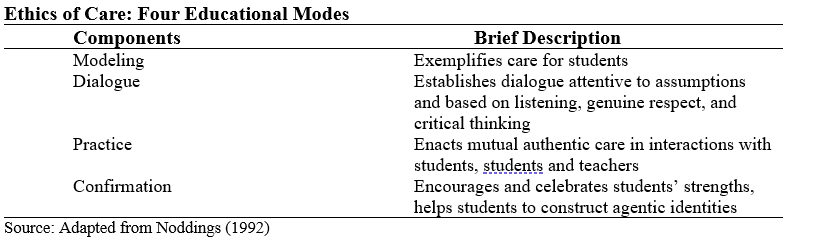

Noddings (2003) and Gay (2018) distinguish between caring for (authentic caring) and caring about (aesthetic caring). According to Noddings (1984), caring about or aesthetic caring is: 1) characterized by some distance; 2) directed to the public realm; and 3) characterized by empathy as foundational to people’s sense of justice and an ethic of care. Caring for or authentic caring combines empathy with purposeful action that responds to the needs of the cared-for (Barek, 2020; Noddings, 1984, 2003). Table 1 offers a snapshot of Noddings’ (1992) four approaches to enacting care in educational settings: modeling, dialogue, practice, and confirmation.

Table 1

Ethics of Care and Radical Self-Care Frameworks

Ravitch (2020a, 2021) identifies radical compassion and radical self-care as necessary for ethical educational leadership and pedagogy. Ravitch foregrounds the urgent need for educators to combine an ethic of care and radical self-care in times of precarity such as now. This is timely and generative since critiques of Noddings’ ethic of care include that it ascribes little importance to educator self-care except as a means to support learners (e.g., Engster, 2004; Tilleczek, 2014). Moreover, the notion of self-care itself has been mis/equated with selfishness. This is problematic since self-care is vital to personal wellbeing and professional excellence and sustainability.

Ravitch (2020a) avers that educators must centralize radical compassion and radical self-care to improve mental health and wellbeing, which includes examining and re-conceptualizing beliefs and biases relating to social identities and power. This creates the condition for educators to foment and support positive change—through intentional self-reflection, collaboration, and equitable communication that attends to power, identity, agency, and equity. Ravitch (2021) frames educator self-care as vital to educational justice and humanization rather than as selfishness. Similarly, Tilleczek (2014) states that “far from being self-interested at the expense of others, the care of the self is bound to the care of others, and to criticize it in opposition to selflessness is to misunderstand the deeply relational nature of the Socratic ethics of care” (p. 1).

In line with Ravitch (2021) and Tilleczek (2014), Nicol and Yee (2017) assert that self-care comprises a form of political resistance:

Our scholarship, teaching, and activism are part of a larger collective struggle for social justice for those who are marginalized, silenced, and disempowered. We know that we cannot sustain ourselves if we are physically exhausted, emotionally drained, and spiritually dead. Therefore, when embarking on our careers…we made commitments to each other to resist sacrificing our health and fulfillment as holistic beings and to “not let this job kill us. (p. 135)

Combining ethics of care (Noddings, 1992) and radical compassion and self-care frameworks (Ravitch, 2020a) addresses the need for teacher and leader self-care and centralizes learners from a standpoint that seeks to foster care as a building block to educational and social transformation.

Care, compassion, and empathy are sometimes used interchangeably, yet care for students involves active intervention in educational settings. Recently, critics of empathy (e.g., Bloom, 2017; Prinz, 2011) argue that empathy is susceptible to “morally troubling biases and motivational shortcomings” (Read, 2021, p. 460). We understand this thinking as an artifact of White Western rationality, built on binaries and reductive concepts of both empathy and education. Noddings (2003) and Gay (2018) identify action as necessary for cultivating ethical care in schools. Ravitch (2021) illuminates how radical compassion and radical self-care can actionize intersectional theory to drive educational transformation for equity.

Pedagogies of Care in Higher Education

Care in higher education teaching and learning has received little attention (Walker & Gleaves, 2016). Anderson et al. (2020) aver that “care is arguably implicit in much published literature on effective teaching in higher education” (p. 3) and point to a recent increase in scholarly interest in care. White (2017) compares Western and non-Western perspectives on compassion and care in education, concluding that while the latter is positive, Western perspective is negative, seeing it as detracting from academics. The recent emergence of care in higher education discourse can be understood as a recovery of compassion in teacher-student relationships and its contribution to positive educational experiences and learning outcomes (Robinson, 2018).

In Canada and the United States, university students are increasingly racially, ethnically, culturally, socially, economically, and linguistically diverse. Pedagogies of care are of particular importance in higher education given that institutional and structural oppression work in diffusion effect for traditionally marginalized students (Ravitch, 2020a). There is urgent need for transformative pedagogies (Lopez & Olan, 2018) enacted by agentic and racially literate instructors (Priestley, Biesta, & Robinson, 2015; Ravitch, 2021) who are responsive to learners, create caring relationships that promote learner wellbeing, and are compassionately responsive to instructional and learning challenges imposed by the pandemic (and then beyond). Through efforts at reciprocal transformation, educators concurrently humanize ourselves and our students.

In response to educational disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, humanizing pedagogies (Ravitch, 2020a), specifically care pedagogies, have been centralized in higher education.We have collectively reimagined learning spaces during these precarious times. The pandemic has taught us that the consequences of global crises disproportionately affect historically marginalized students. Focus on teacher-student relationships has intensified since face-to-face interactions previously taken for granted are interrupted in order to alleviate pandemic impact on learners. Emergent frameworks include pedagogies of care (Noddings, 1992), Flux Pedagogy (Ravitch, 2020a), Trauma-Informed Healing-Centered Pedagogy (Ginwright, 2018; Ravitch, 2020b), and Culturally Responsive Teaching (Gay, 2018).

Flux Pedagogy

Flux Pedagogy (Ravitch, 2020a) foregrounds responsiveness to students’ holistic needs. This framework supports educators in learning to design and enact humanizing and transformative pedagogy responsive to emergent needs. Flux Pedagogy refers to the integration of relational and critical pedagogy frameworks into a transformative teaching approach in times of radical flux. It is constructivist, student-centered, relational, and reflexive; a humanizing pedagogy that examines the goals and processes of education with a goal of mutual growth and transformation; and, a framework for “balancing radical compassion for students…with high-yet-humanely-calibrated expectations for learning” (Ravitch, 2020a, p. 1). The key dimensions of Flux Pedagogy are: Inquiry Stance; Trauma-Informed Healing-CenteredPedagogy; Radical Compassion and Radical Self Care; Responsive and Humanizing Pedagogy; Critical Pedagogy; Racial Literacy; and Brave Space Pedagogy.

Trauma-Informed Healing-Centered Pedagogy

A central dimension of Flux Pedagogy is trauma-informed pedagogy, which requires knowledge of trauma and a commitment to informed action (Stephens, 2020) including understanding how trauma–including identity-based trauma– impacts student development, behavior, relationships, presentation of self, learning, and academic achievement. Ravitch (2020b) introduces trauma-informed healing-centered pedagogy based on Dr. Shawn Ginwright’s (2018) healing-centered engagement framework, which critiques traditional trauma-informed pedagogy as disaffirming to students of color, offering in its place a culturally responsive, assets-based approach to trauma. Pak and Ravitch (2021) assert that trauma-informed pedagogy,

Foregrounds understanding trauma – personal, communal, and generational – and its social and emotional reverberations, cultivating a learning environment comfortable to those who’ve experienced trauma, and recognizing the resilience and resources of individuals and communities who have experienced or are experiencing trauma (p. 18).

Core values that guide a trauma-informed pedagogy include “safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, and empowerment” (Fallot & Harris, 2009, p. 3). Like Ravitch (2020b), Stephens (2020) links trauma-informed pedagogy and care, explaining that a trauma-informed approach necessitates a shift from confrontation to care in higher education. Importantly, educators’ mis/understandings of trauma impact their “pedagogical effectiveness and ability to nurture the best learning in their students” (Stephens, 2020, p. 1).

Culturally Responsive Teaching

During the pandemic, equity issues such as access to technology and tutoring support came to the forefront of education. Smith (2020) suggests that Culturally Responsive Teachingpedagogies (Gay, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 1995) counter inequity and support the resilience and resources of individuals and communities disproportionally affected by structural oppression (Ravitch, 2020a). Gay (2018) contends that caring teachers “expect (highly), relate (genuinely), and facilitate (relentlessly)” (p. 57). Gay (2018) introduces the concept of Culturally Responsive Caring as fundamental to an education system focused on caring for student wellbeing. Caring about relates to attitude, while caring for relates to practice and action. These are interrelated. Gay (2018), states “while caring about conveys feelings of concern for one’s state of being, caring for is active engagement in doing something to positively affect it. Thus, it encompasses a combination of concern, compassion, commitment, responsibility, and action” (p. 58).

Educators need to be culturally responsive and thus, teacher education and faculty professional development must teach how this is enacted in classrooms from pre-school through graduate school. Otherwise, students, teachers, and faculty from historically marginalized groups will continue to feel unwelcomed, underrepresented, alienated, and overburdened when responding to their own and their students’ marginalization. Teacher education and faculty professional development must improve practice and pedagogy; challenge assumptions; and become pedagogically responsive to deeply segmented institutional oppression based on structural racism and the relentless microaggressions it nurtures in higher education spaces.

Concluding Inquiry: What does COVID-19 make possible for care in education?

The COVID-19 pandemic and the educational disturbances it engenders have opened our eyes to the harmfulness of unjust traditional pedagogical practices and the possibilities for ethical and equitable schooling; they remind us what matters most: relationships, care, and compassion. As a result, care for others––particularly students––and care for self, as dimensions of humanizing pedagogy, are currently foregrounded in educational discourse. This emergent understanding must be actionized and internalized, not forgotten, as we return to routines.

References

Acevedo, B. (2020). Pedagogy of Care in Times of Crisis - ARU.

Anderson, V., Rabello, R., Wass, R., Golding, C., Rangi, A., Eteuati, E., Bristowe, Z., Waller, A. (2020). Good teaching as care in higher education. Higher Education, 79(1), 1–19.

Barek, H. (2020). Exploring the experiences of high school Syrian refugee students with interrupted formal education and their teachers in ELD classrooms. Electronic Thesis & Dissertation Repository. 7532.

Bloom, P. (2017) Against empathy: The case for rational compassion. Random House.

Engster, D. (2004). Care ethics and natural law theory: Toward an institutional political theory of caring. The Journal of Politics, 66(1), 113-135.

Fallot, R. D., & Harris, M. (2009). Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care (CCTIC): A self-assessment and planning protocol.

Freire, P. (2005). Teachers as cultural workers: Letters to those who dare teach. Westview.

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd Ed.). Teachers College Press.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

Ginwright, S. (2018). The future of healing: Shifting from Trauma-Informed Care to Healing-Centered Engagement. Medium.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491.

Lopez, A. E., & Olan, E. L. (2018). Transformative pedagogies for teacher education: Moving towards critical praxis in an era of change. Information Age Publishing.

Monchinski, T. (2010). Critical pedagogies and an Ethic of Care. Counterpoints, 382, 85-135.

Mortari, L. (2016). For a Pedagogy of Care. Philosophy Study, 6(8), 455-463.

Nakkula, M. J. & Ravitch, S. M. (1998). Matters of interpretation: Reciprocal transformation in therapeutic and developmental relationships with youth. Jossey-Bass.

Nicol, D. J., & Yee, J. A. (2017). “Reclaiming our time”: Women of Color faculty and radical self-care in the Academy. Feminist Teacher, 27(2-3), 133-156.

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics & moral education. University of California Press.

Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education Teachers College Press.

Noddings, N. (2003). Happiness and education. Cambridge University Press.

Pak, K. & Ravitch, S. M. (2021). Critical Leadership Praxis for educational and social change. Teachers College Press.

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: What is it and why does it matter? In R. Kneyber & J. Evers (Ed.), Flip the system: Changing education form the bottom up (pp. 1–11). Routledge.

Prinz, J. (2011). Against empathy. The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 49(1), 214–233.

Ravitch, S. M. (2020a). Flux Pedagogy: Transforming teaching and leading during Coronavirus.

Perspectives on Urban Education, 17(4), 18-32.

Ravitch, S. M. (2020b). Moving to Healing-Centered Engagement: Reimagining Trauma-Informed Leadership. TraumaVenture.

Ravitch, S. M. (2021, February 16). Pedagogies of care in higher education. Conversations on pedagogies in teacher and higher education – Community of Practice (CoP).

Read, H. (2021). Empathy & common ground. Ethical theory & moral practice, 24(2), 459-473.

Robinson, S. (2018). The Pedagogy of Compassion at the heart of higher education. Journal of Global Responsibility; Bingley, 9(1), 130–134.

Smith, J. M. (2020). Practice what you preach: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy during COVID-19. Issues in Teacher Education, 29(1-2), 23–34.

Stephens, D. W. (2020). Trauma-Informed Pedagogy for the religious and theological higher education classroom. Religions, 11(9), 449.

Tilleczek, W. (2014). The connection of the care for self and other in Plato’s Laches. Pseudo-Dionysius, 16(1).

Walker, C., & Gleaves, A. (2016). Constructing the caring higher education teacher: A theoretical framework. Teaching & Teacher Education, 54, 65–76.

White, R. (2017). Compassion in philosophy and education. In P. Gibbs (Ed.), The pedagogy of compassion at the heart of higher education (pp. 19-31). Springer.

Conditions in the world are changing, so researchers need to be responsive to participants. Find a practical, thoughtful post from Dr. Sharon Ravitch.