Inspiring wise action: Practices for storytellers of all kinds

By Lydia Hooper

Ms. Hooper uses her data visualization and research communication skills as a UX designer for the company Agile Six and has extensive experience as a freelance evaluator and designer. In June and July 202 MethodSpace focused on research-oriented careers in and out of academia.

I remember the exact moment it dawned on me. Actually, there were two, though in many ways one eclipsed the other. Both seminal moments occurred in a telling place: a classroom...

The first teacher was a man whose commitment to science was matched only by his passion for justice. He'd assigned us, his students, several readings that went into great detail (as scientific papers generally do) about the apparent fate of our planet. If you've ever read a book by Bill McKibben or even Rachel Carson you know all too well how frightening numbers can sometimes be. So when he turned to us that morning and posed, "So what do you guys think?", it is no wonder that all he got was crickets.

I looked into my peers' faces and sensed what they struggled to verbalize: they felt scared, hopeless, paralyzed. That's the moment that changed everything for me. Because I realized that that was not how I felt. Years of training and practice kicked in and my hand quickly shot up in the air. "I think we need to do something!"

What training and practice am I referring to? Well that brings us to the twin moment: another classroom, an entirely different subject. This teacher was a man of precision too, though he exercised it not in the study of the physical world but rather of the imagined one. His passion for the power of aesthetics was matched by his unspoken belief that only those who were fully committed to their craft were worthy of such power.

It should come as no surprise then that he had assigned us not something to consume but something to create. We'd been given the liberty to tell the story that was calling us to and, importantly, some constraints about how we could tell it. Rather than posing a question, his challenge was arguably more difficult: "Show us what you got." Crickets would be the surest guarantee of failure.

Instead of peering into their faces, I stared at my peers' work, eager to see the exciting stories they'd chosen to reveal. Again I was changed, though not in the way I'd expected. Their stories weren't... well, stories. They were merely pictures. I wondered if again I was the only one who felt something different. I couldn't shake the feeling that these so-called stories were just too flat. I also wondered if I was the only one who felt they'd poured their heart and soul into the story they'd created, less afraid of saying too much for fear of not saying anything at all. With so many stories to tell, so many transformations we need to inspire, I thought to myself, "I think we need to say something, something important."

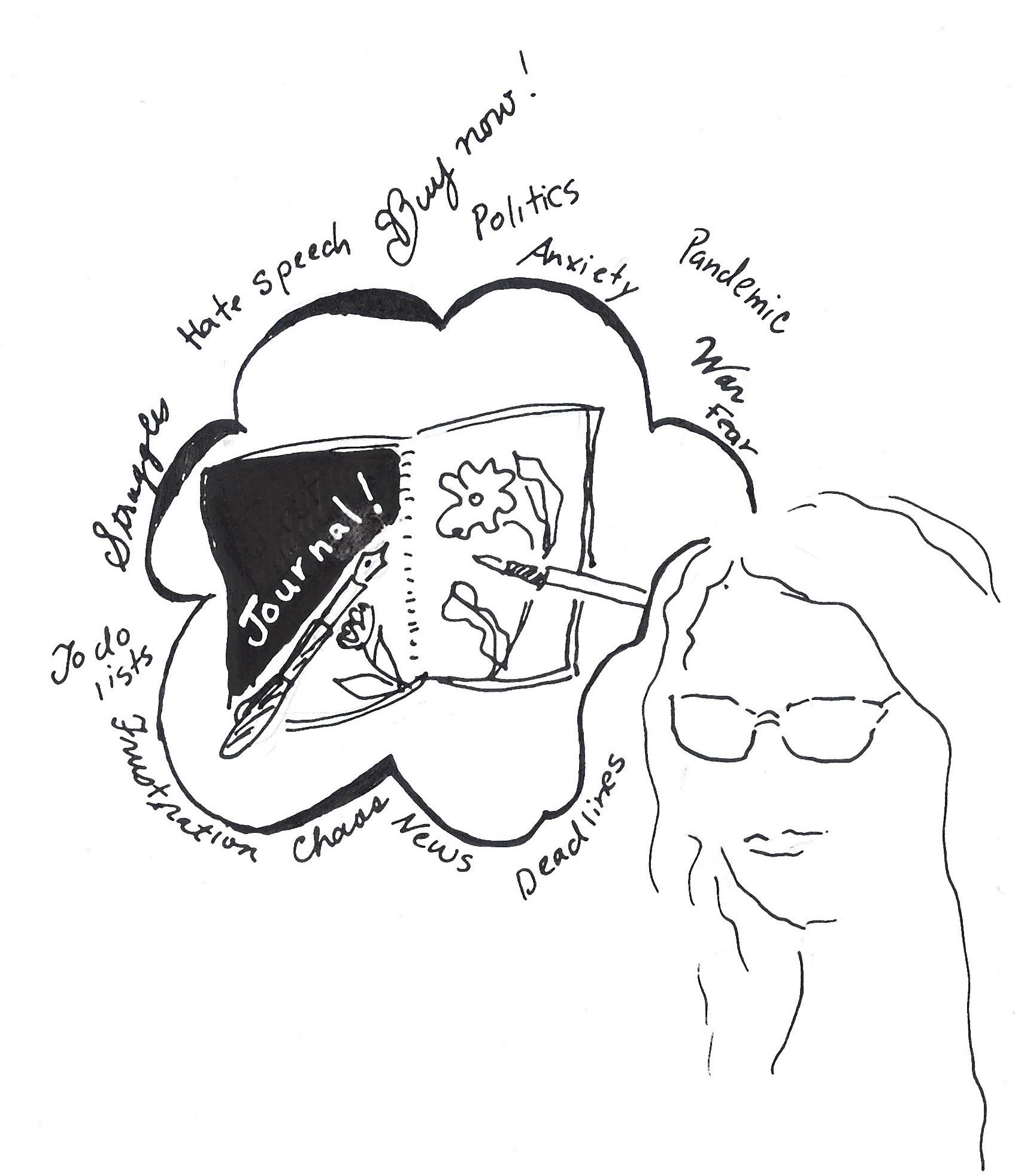

The duality of these moments not only have continued to stay with me, they set me on a path that I blazed for myself and have remained on. Many years later, I still see those frozen faces when I teach workshops on telling stories with data and those flat pictures continue to haunt me nearly everywhere I go, in advertisements and periodicals, on websites and social media pages.

I feel so blessed to have received both an appetite for learning and a compulsion to share, and in this spirit of gratitude, I want not only to share this story, my story, with you, but also some useful ideas for how you might practice raising your hand and saying something important. I consider myself to be a lifelong student, so I hope you will consider my suggestions as ones from an untraditional peer. In my experience, most folks spend time in only one of the aforementioned classrooms, so I've broken my tips down in a simple way that speaks to both the scientifically and the creatively inclined.

Practices for the Analytical

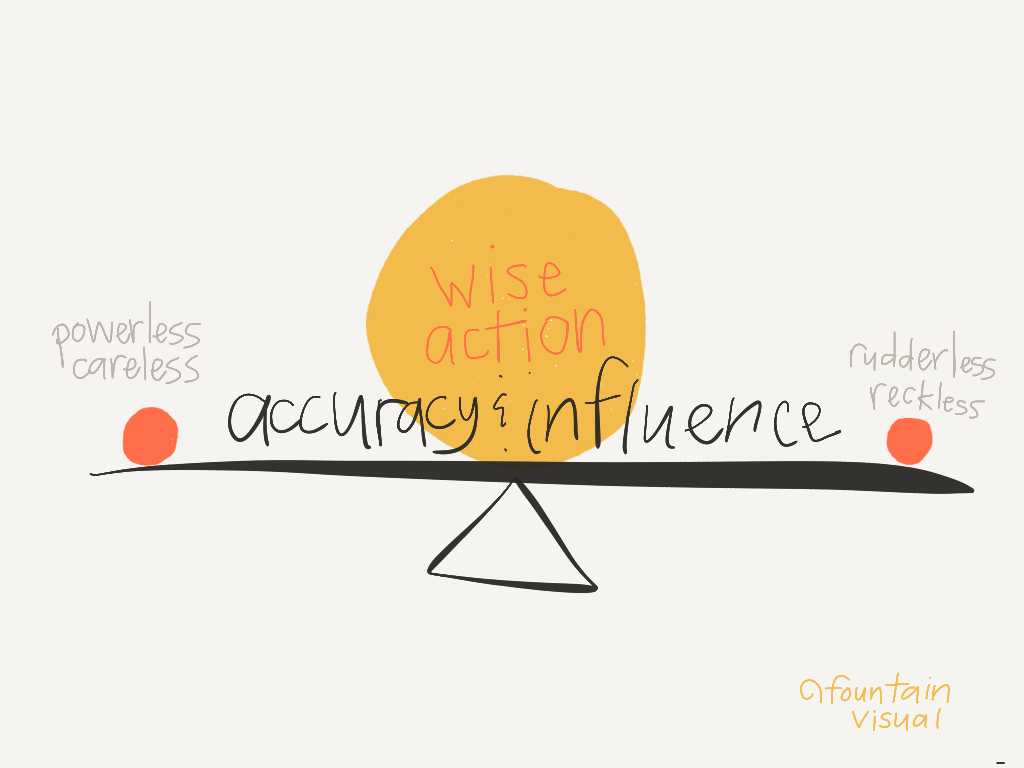

Thinking: It is necessary to persuade. When I teach workshops about data storytelling for evaluators and other data-minded folks, at some point in our process someone usually says something like: "But I'm supposed to be objective. It isn't my job to propose solutions." This may be what you've come to believe, I tell them, but it is critical to help others not only have numbers, but to help them make meaning of them. It is my belief that in order to do so, one must accept that no one is truly objective and that numbers serve no real purpose if not to help us make better decisions. Staying "neutral" doesn't help us make better decisions, it leaves us paralyzed with information overload. If we want to get closer to solving problems like climate change or inequity, we need to make those solutions crystal clear.

Doing: Make what you can and make it again and again and again. I know it takes considerable effort to just collect and organize reliable, complete data, and that when all that work is done the temptation is to rest on our laurels. The truth is that when that beautifully arranged spreadsheet is ready to go, that is when the real work begins. Too much data ends up on a shelf, far from the people who could make better decisions if only they knew better, because no one bothered to show it to them in a way that makes sense and helps them take action on it. One simple, clear bar graph is loads better than a 40-page report filled with jargon and extensive tables. The only way to get better at making clear and simple charts is to keep making them, one by one by one...

Letting go: Perfectionism, otherwise known as the enemy of creativity. The reason we don't keep making them is that we know we can't do it perfectly. When we look at someone else's apparently perfect infographic or slide deck or dashboard, we forget that there were so many bad ones that got created before the great one we're looking at (and that the creator will still look back years from now and see the "perfect" one's obvious flaws). The more bad ones we're willing to blunder through, the more quickly the great ones will emerge. Perfect is a myth.

Practices for the Creative

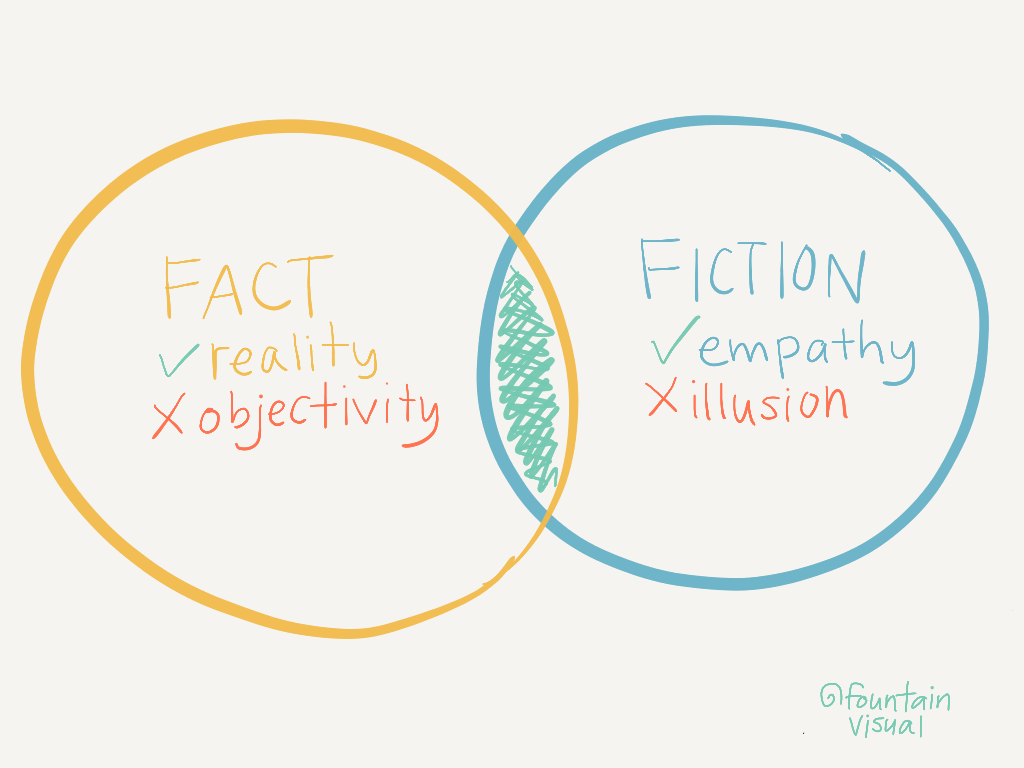

Thinking: It is necessary to tell the whole truth. As creatives, we love dreaming, playing, and making in the land of fiction. We are drawn to the fantastical, whimsical, and impossible. We don't need to stop any of that. But we do need to believe that reality is just as interesting, fun, and inspiring. We also need to understand that too often we contribute to reality seeming to be vacant, deceiving, or, worst of all, boring. We have an incredible power to make the world we see. Let's make it honest. Let's stop telling half-truths (even when someone's paying us to, even when it's easier to, even when we really want to) because we deserve better. We deserve to have the chance to understand this world in all it's complex, contradictory glory and to help others understand it too. We love thinking big, and details really matter. Don't just draw a shape that looks like a beautiful, iconic tree, describe an organism that produces oxygen from sunlight and supports an ecosystem of microbes and animals beneath the earth.

Doing: Think carefully and thoroughly and with others (not for them). Telling the whole truth usually means we need others to help us see and understand it first. If we hide away in our creative caves, we not only protect ourselves from what we don't know, we prevent those we impact from knowing more too. Telling rich stories filled with anecdotes and information requires more thought about how to frame them and how to present them in ways that will help others connect ideas and take wise actions. Too often we use our creative tools to show people what we want them to see, or what they want to see, rather than what they need to see. We need to slow down and sometimes even pause our creative engines and take time to think things through, working closely with others throughout our process to ensure clarity and accuracy.

Letting go: The belief that self expression is the primary goal. Working closely with others, making an effort to describe information in very specific, intentional ways means we may need to let go of our tight grip on being "the visionary" or the "artist" we've been conditioned to be. This doesn't mean we let go of our strengths - thinking big, outside-the-box, imaginatively, aspirationally - it means we appreciate that this thinking must also be grounded in reality and balanced with practicality, which is much easier when we are open to working collaboratively. The myth we need to let go of is that of the singular genius. It is my belief that our greatest strength, in fact, is not our ability to archetypically model our culture's obsession with individualism, but rather to connect with the heart of our humanity, what makes us all connected and equal.

No matter your strengths, I hope these practices will invite a dawning for you. Let yourself be taught that with a commitment to truth and a belief in our collective creative capacities, we not only can keep going when we each get stuck, but we can keep our colleagues, communities, and world moving forward with wisdom too.

About Lydia Hooper.Lydia is a regular guest contributor to MethodSpace. See:

For the past decade, Lydia has been working at the crossroads of science, education, and design in a dogged pursuit to discover how we can best come together to create the change we collectively need. She is committed to supporting creatives, visionaries, innovators, change agents, and civic leaders in being brilliantly creative and beautifully collaborative by sharing knowledge and practical tools. You can easily become one of her beloved patrons on Patreon and get access to hundreds of articles, visuals, interviews, worksheets and more about topics such as psychology, storytelling, and facilitation. Just visit patreon.com/lydiahooper and choose the membership tier that works best for you (starts at $2 a month). You can follow her on Medium and join her FREE virtual Work That Reconnects workshop.

Should you blog about your research? What types of academic blogs serve what purpose?