The challenges of co-creation: some reflections on programming and (e)valuating MAKE@StoryGarden

by Patrycja Kaszynska and Adam Thorpe

The challenges of co-creation: some reflections on programming and (e)valuating MAKE@StoryGarden

MAKE @ Story Garden is a public space for creative collaboration in Somers Town and St Pancras in central London. It is a meanwhile (temporary) place with workshop and making facilities, with an attached programme of arts and design activities for local people, arts school students and staff, and the public at large. At the time we are writing this note, the space is fully managed by the local community but the project we are describing pertains to the period when it was led by a partnership between a local community association, a local council, an international developer and an arts college (Central Saint Martins), part of the biggest art and design university in Europe (UAL). As such, MAKE was a testbed for collaborative ways of working between organisations across different sectors. The evaluation of the project was also an opportunity for a humanities researcher (with a background in philosophy and art history) and a design researcher (with a particular interest in participatory design and social innovation) to work together, alongside other colleagues in the delivery team.

MAKE at Story Garden. Photo by Adam Razvi, courtesy of Central Saint Martins, UAL

MAKE applied two distinctive methodological approaches.

On the level of design, delivery and programming, the project used a bespoke methodology originating in participatory design and social innovation. On the level of evaluation, the approach was custom made too as no ready-made approach could cope with capturing the value created at MAKE @ Story Garden.

On the level of programming and as conceived by the academic leading the delivery (Prof, Adam Thorpe), MAKE was a structure that brings together people, resources and policies. Rather than a project, it is perhaps more accurate to describe it as a platform that supports the building of relationships between both, individuals and organisations, developing organisational capacity and strategic alignments across different sectors in the process. In this sense, MAKE is an example of an ‘infrastructuring’ approach which draws on the traditions of Participatory Design (PD) and ‘co-design’ (described by digital civics and design researchers La Dantec and Disalvo as ‘the work of creating socio-technical resources that intentionally enable adoption and appropriation beyond the initial scope of the design’). The crucial feature of this approach is that, in addition to the creation of artefacts, products and/or services that provide a context and motivation for participation, what is being co-created are relationships, capacities and strategic alignments that afford opportunities for social connection, social inclusion and social innovation (finding new ways of working and living together that are more beneficial for people and planet). As one of the funders put it, ‘MAKE is one big social prescription’.

The choice of infrastructuring as the methodological approach underpinning the programming had implications for how MAKE @ Story Garden could be evaluated. Simply put, MAKE was not built to maximise instrumental gains vis-à-vis narrow objectives, and ‘measuring’ it as if it was would not do it justice. A different way to put this point is that MAKE fostered redundancy (as in superabundance and surplus) rather than efficiency, with an understanding that a superabundance of infrastructure - relational and otherwise - contributes to resilience. The effect of using infrastructuring as a design method combined with relying on arts and design as a vehicle of delivery leads to the situation where potentialities are created with only some being translated into actualities. Maximising short-term gains with respect to a narrow range of pre-determined impact registers is simply not the main motivation and, hence, redundancies in the system are created, intentionally, as spaces for experimentation, learning and contingency. The value produced is greater than the value realised. ‘Almost always knowingly and intentionally undersold’ is probably not a great slogan, but yet, one which captures well an operational strength and, paradoxically, a weakness of MAKE from the point of view of standard evaluation.

From the beginning, the researcher leading the (e)valuation activities (Dr Patrycja Kaszynska) stressed the limitations of standard evaluation approaches concerned with assessing performance against fixed objectives. Still, MAKE was a partnership project with a set of objectives to satisfy. A proposal was made that, in addition to the standard objective—and outcome—based reporting (which was well placed to meet the accountability requirements set by the partners), a more open-ended form of ‘mapping’ was to be introduced. Accordingly, the proposed (e)valuation design consisted of two parallel strands: 1) a retrospective one grounded in the ‘log frame’ approach; and 2) a prospective one anchored in the ‘Outcome Mapping’ approach.

The proposal was thus to simultaneously monitor the outcomes against the agreed objectives; and to track progress against the expectations articulated by those affected by the project - the so called ‘boundary partners’ (a technical term in the Outcome Mapping approach proposed in the 2001 book by Sarah Earl, Fred Carden and Terry Smutylo Outcome Mapping: Building Learning and Reflection into Development Programs). The mapping/tracking – or ‘following the actors’ to borrow an oft-cited quip from Latour (a philosopher, anthropologist and sociologist who contributed to the development of actor-network theory) - was a response to the realisation that a lot of value produced through infrastructuring is emergent (and so, cannot be predicted in advance) and latent (present as a capacity but not actualised in the given time frame). This ‘value-based’ way of working (assuming that people capitalise on the opportunities given by acting in line with their values and so directing their actions accordingly) was also introduced to reflect the participatory ethos of MAKE and the fact that MAKE, above all, was about co-creation.

MAKE at Story Garden. Photo by Adam Razvi, courtesy of Central Saint Martins, UAL

Co-Creation in Practice

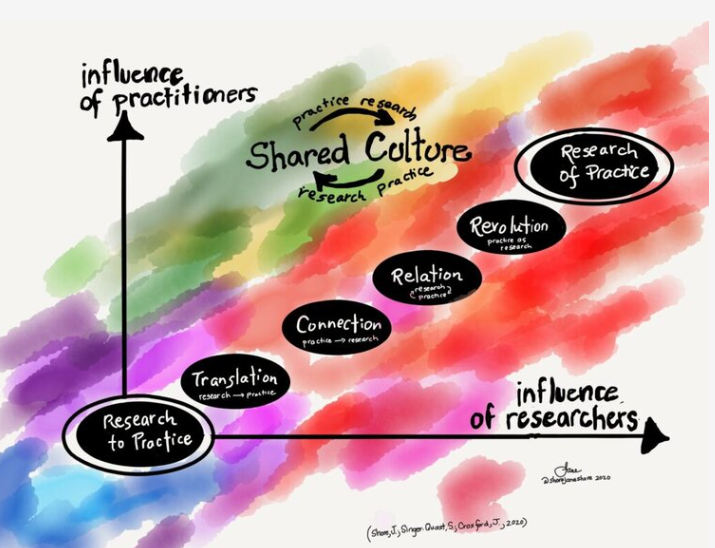

Co-creation is one of those words that has been defined in several different discourses - including management and marketing, clinical practice and arts and humanities research - and has different meanings in different contexts. For the purposes of our project, co-creation meant that value is generated collaboratively through the interactions between the actors (those who experienced MAKE) and the evolving networks forming the infrastructure (which included humans and non-humans). Understood in these terms, co-creation, of and in MAKE, necessarily led to plural value articulations with the actors interpreting opportunities and influencing change over time in line with their values. In recognition of this, the project was called ‘(e)valuation’ rather than ‘evaluation’.

Those who read the full report will learn about the challenges of programming and of (e)valuating co-creation. The delivery of MAKE was not easy; and the evaluation was peripatetic too. The former gave raise to questions such as: How much control is enough but not too much?; Can infrastructuring be managed?; How to govern by a network? Regarding the latter, there were not just big conceptual questions but also practical issues, such as that the partners found the amount of time required to implement the Outcomes Mapping through workshops daunting (this is the approach proposed by Earl et al). This, coupled with the Covid pandemic, meant that the outcome mapping was not implemented as initially intended, nor were participant journals used, which was offered as the second-best solution. Rather, the accounts of how value unfolded form MAKE were provided by narrative accounts from the participants. The authors now collaborate on developing the narrative methodological approaches using the perspectives from design and the humanities. In spite of the challenges identified and experienced, the authors remain convinced that finding ways of practicing and valuing co-creation, and the methodological innovations this entails, are central to practice research motivated by the ambition for more equitable and inclusive futures.

Tips on grading and marking to make it relevant and useful for students’ future research.