Who identifies research problems?

by Janet Salmons, Research Community Manager for SAGE Methodspace

Let’s begin this quarter’s exploration of research design by raising questions about how the research problem or topic is defined, by whom.

Whether you decide to conduct a large, complex study or a small project for a course assignment, you must begin by deciding what to study.

The research problem addresses what researchers perceive is wrong, missing, or puzzling, or what requires changing, in the world. Presentations of the research problem typically set the stage for the study that will be, or that was, conducted by offering evidence that the problem exists and for whom and by establishing the significance of the problem and why it requires formal inquiry. (Given, 2008 p. 734)

Learn more! Register now for a free webinar on January 31, 2024, How to connect the study’s methodology with publication options.

What evidence signifies the need for formal inquiry and serves as the foundation for a research design? As a researcher, how will you perceive what is wrong, identify important concerns that are missing from scholarly literature, or find critical issues that require change in the world? As researchers, are we the only ones who can and should identify problems that merit study?

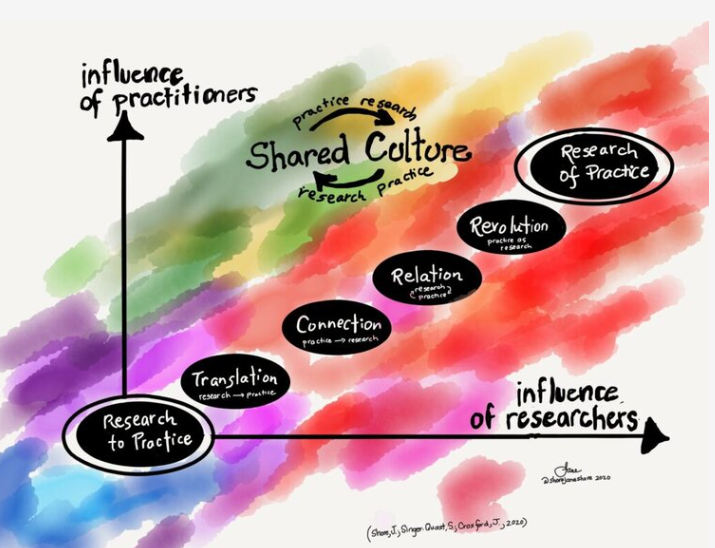

In 2022 Methodspace focused on Research Relevance and explored questions about whether and how scholarly research matters. The implications go beyond research impact, or perhaps pre-empt considerations of impact, with the suggestion that we think about how, where, and for whom research matters from the very beginning. As McCormack (2011)observes:

[I}t is fair to say that the debates about impact in most research disciplines largely adopt a linear and traditional model of knowledge production, with ‘impact’ considered towards the end of projects and usually as part of (passive) dissemination strategies. Such approaches promulgate the distinction between knowledge producers and knowledge users. (p. 112)

How can consideration of relevance to the field, to practice, to impactful change-making in the world be woven into the formulation of research topics and problems? In the 2007 book Engaged Scholarship: A Guide to Organizational and Social Research, Andrew Van de Ven suggested that we need to engage with the people who have direct first-hand knowledge and experience with the issues and contexts associated with the inquiry. He coined the term “engaged scholarship” and defined it as:

a participative form of research for obtaining the advice and perspectives of key stakeholders (researchers, users, clients, sponsors, and practitioners) to understand a complex social problem. By exploiting differences in the kinds of knowledge that scholars and other stakeholders can bring forth on a problem...engaged scholarship produces knowledge that is more penetrating and insightful than when scholars or practitioners work on the problems alone. (Van de Ven, 2007 p. 9)

Van de Ven’s (2007) approach makes the case for principles of engagement with stakeholders and others who have personal or professional knowledge. He points out that the less you know the greater the need to engage with others who can instruct and ground you in the problem domain (p. 268). Since 2007 many forms of engaged scholarship have emerged that apply these principles in various fields of study, such as:

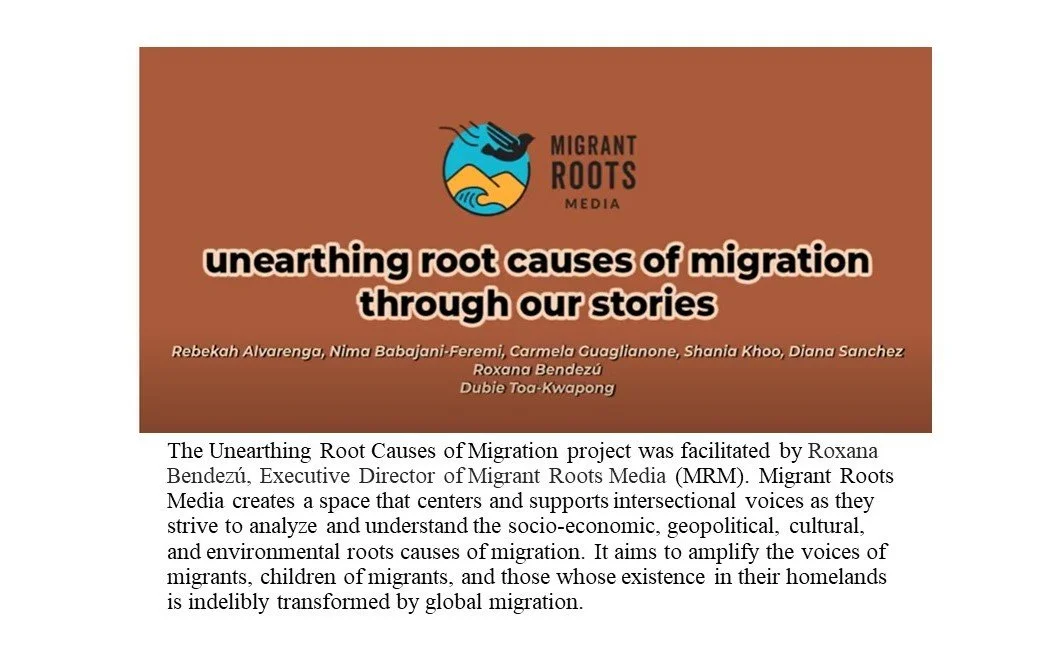

Community Engaged Scholarship (CES): researchers and community stakeholders’ contributions, in their respective areas of expertise, co-create knowledge that addresses community-identified cares and concerns, as well as serving the public good (O’Meara, 2018).

Publicly Engaged Scholarship (PES): In fields of public administration and public policy, “scholars have responded to changing demographics within higher education as well as the contemporary demands of societies to address challenging issues of inequality, environmental degradation, and democratic exclusion, among others, by developing less hierarchical and more cooperative forms of scholarship” (Eatman et al., 2018) p. 532.

Van de Ven advocated that these principles should underpin all research methodologies and for this to be an explicit criterion in the establishment of research designs. That said, the degree of engagement might vary greatly. In some cases it involves developing relationships by meeting and talking with people, or observing the culture, community, or organization. For others it will involve engaging with relevant reports, publications or media – outside of scholarly literature – by people close to the situation. These four categories, adapted from Van de Ven’s descriptions, offer some options:

Informed Research: Research problem is identified and defined with the advice and feedback of stakeholders. Researcher is responsible for conducting study activities.

Collaborative Research: Research problem is identified and defined by the researcher and project partners. Research team includes stakeholders who share study activities to co-produce knowledge.

Action Research: Research problem, and intentions for interventions or change to address it, are identified and defined by the researcher and project partners. Action research, or participatory action research, includes stakeholders in research design, plans, conduct, and dissemination/implementation. Stringer and Ortiz Aragón (2020) introduce their excellent text with this key point: “Action research works on the assumption that those closest to the impact of [contemporary] issues are “experts” in understanding many of the realities of their own lives and should therefore be directly involved in addressing them” (p. 6).

Design/Evaluation Research: Problem is identified and defined by the client who engages the researcher. Researcher develops and evaluates the client’s policy, program design or activities.

The degree of engagement shifts with each of these options, moving from input and feedback from stakeholders to actively sharing responsibilities and decision-making. With informed One is not inherently better than another, the appropriate choice will fit the particular situation. For example, not everyone has the time and resources necessary to build relationships needed for collaborative or action research. However, as researchers, any stakeholder engagement offers an opportunity to learn from and with those who know, experience, and understand the situation and can thus help define a more relevant problem to study than we might otherwise determine.

Questions to consider to increase engagement at the problem definition stage

Who understands the domain you want to study, the population, the setting, and/or the culture important to the topic(s) of interest?

Who is feeling the impact of issues at hand, and who will feel the impact of change?

What do they read: are there publications, blogs, newsletters, reports, or other sources that get into the issues at hand? When you look at these sources, are there respected experts or thought leaders who articulate the issues?

Where do they share concerns, thoughts, feelings about the issues? Online or local groups?

Do stakeholder discussions point to other disciplines or literatures you should explore to get a fuller understanding of the problem domain?

If/when you meet with stakeholders, listen!

If you want to ask for input, feedback, or collaborative involvement, what can you offer in return? Beyond the usual incentives, can you offer to share findings, practical recommendations, training, or other assistance?

Avoid “helicopter” research, especially when crossing cultures. See the Global Code Of Conduct For Research In Resource-Poor Settings.

Learn more!

Find original posts, curated open-access reading lists, video interviews and more on action, collaborative, and evaluative research in these Methodspace posts from the archives.

References

Eatman, T. K., Ivory, G., Saltmarsh, J., Middleton, M., Wittman, A., & Dolgon, C. (2018). Co-Constructing Knowledge Spheres in the Academy: Developing Frameworks and Tools for Advancing Publicly Engaged Scholarship. Urban Education, 53(4), 532-561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918762590

Given, L. (Ed.). (2008). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. SAGE Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.

McCormack, B. (2011). Engaged scholarship and research impact: integrating the doing and using of research in practice. Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(2), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987110393419

O’Meara, K. (2018). Accurately assessing engaged scholarship. Inside Higher Education.

Stringer, E. T., & Aragón, A. O. (2020). Action research. SAGE Publishing.

Van de Ven, A. H. (2007). Engaged scholarship : A guide for organizational and social research. Oxford University Press. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/capella/docDetail.action?docID=10194261